Illustration as Language

Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction to Illustration as Language

Illustration can operate as a language in the sense that illustrations can convey meaning whether that be through symbols, visual representations, cultural references, and/or stylistic choices1. However, not all illustration does convey meaning other than depiction of the subject. Much like verbal languages, visual communication can be coded enabling artists to communicate complex ideas and narratives, e.g. the use of metaphor both visually and verbally has the same function. In their book ‘Reading Images’, Gunther Kress & Theo van Leeuwen compare visual communication to writing. They explore how the relationship between the two is not directly proportional in that visual communication doesn’t perform the same linguistic role as written language but that they can be compared through their depiction of meaning.

Function of Illustration as Language

As illustration is often presented alongside text it is important to be clear about its function. It can either complement a text (advancing the story and ‘fleshing it out’) or it can literally depict the story (performing an accessibility function – i.e. for readers that may need the visual support). Creating an image that complements a text, thus adding value, is necessarily performed by a human and is where illustrators excel due to their visual imaginations and ability to construct images that human readers may connect to emotionally (decidedly lacking in AI. Image Generation). Not just images that ‘look good’.

Symbolism of Illustration as Language

Symbolism plays a pivotal role, as artists imbue objects, colours, and shapes with meaning, allowing for nuanced expression beyond verbal description. For instance, a red rose might symbolise love or passion, transcending linguistic boundaries. Symbolism can also be geographically dependent – e.g. a snail being used for a sign to ‘go slow’ in countries that have snails but not in those that don’t, although this is subject to the universality of the Internet in 2024 as are many cultural differences in symbolism.

Style in Illustration as Language

An artist’s style functions as a dialect within this visual language, shaping how messages are conveyed and perceived. It has been argued that the style rules that apply to an illustration are akin to grammar within text2. Whether realistic, abstract, or somewhere in between, each style carries its own vocabulary and grammar, influencing interpretation. I believe that this is an important reason for criticism of A.I. art that can be produced “in the style of’ artists who have worked hard to develop their vocabulary.

So, Do You See Illustration as Language?

It is fair to say that, like some poetry/music/cuisine, it can be difficult to ‘read’ some illustration. This can be dependant on a number of factors including the complexity of the image, the sensitivity of the subject matter, the intended audience, inclusion of culturally specific elements, the skill of the artist, the visual literacy of the viewer. For illustration to function most clearly as language it is important to be aware of these factors as relates to the intended audience. How deep do you want your visual communication to be or how bold/controversial/direct/subtle/sensitive/warm/dismissive – it can all come across in the way a subject is painted. While it pays to be careful and deliberate it’s also worth remembering that art can be subjective with people seeing, in an image, what most directly relates to themself.

Blog Search

Illustration Newsletter

Sign up for regular but infrequent updates about my illustration creations.

Will Smith caricature

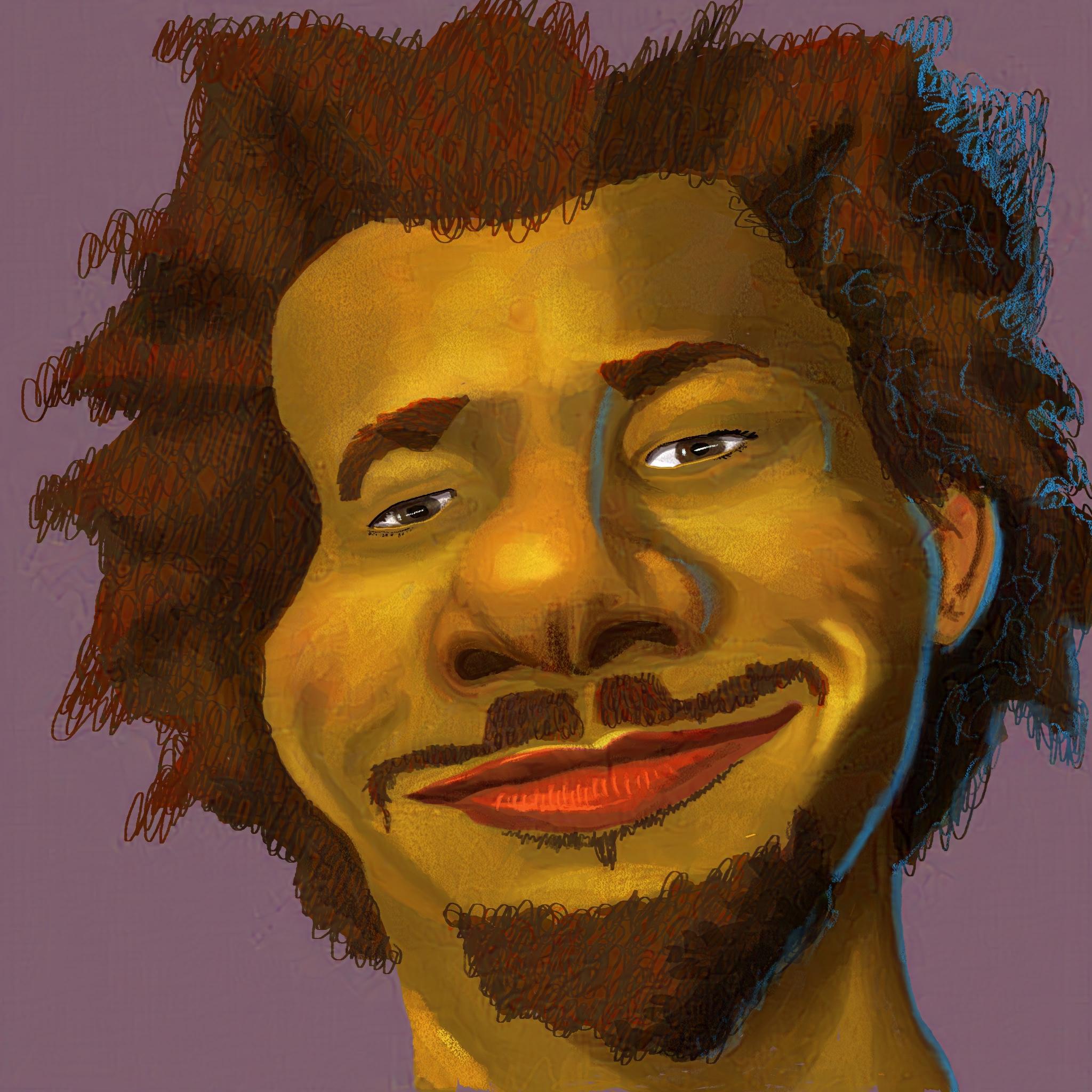

Eric Andre Caricature